Tweezer gates

This semester I decided to erect my own pulpit for delivering my high-effort crappy powerpoint presentations, the UIUC Quantum Information / Atomic Molecular and Optical physics Journal Club (QIAMO). And who better to sing the first round of lullabies than the founder himself, Alex An? So, I dropped everything I was doing in lab and spent a week crafting my magnum opus:

THIS POWERPOINT.

While I didn’t spend as much time on this talk as on my previous Quantum Gas Microscope presentation, I spent proportionally more time thinking about the talk rather than meticulously moving elements around in the Animation Pane.

Finally, I realized in typing this up that I should include a disclaimer here: Despite the jokes, nothing in this powerpoint is meant to offend (though “Rubidium” really should be mentioned in the text…). I wouldn’t spend all of this effort if the paper itself wasn’t interesting.

The paper(s)

- Title: Parallel implementation of high-fidelity multi-qubit gates with neutral atoms

- Authors: Harry Levine, …, Mikhail Lukin

- arXiv:1908.06101

This is the latest work in a long line of success for the tweezer experiment from the Lukin group, a paper-producing machine which I’ve gushed over in my DAMOP post from earlier this year. This experiment has gone from “cool” to “astounding”, and now to the edge of viable quantum computing.

| arXiv:1607.03044 (Science) | arranging a line of single atoms trapped in tweezers |

| arXiv:1707.04344 (Nature) | quantum simulation of many-body physics |

| arXiv:1806.04682 (PRL) | much improved Rydberg lifetimes, two-atom entanglement |

| arXiv:1809.05540 (Nature) | more quantum sims, kibble-zurek quench stuff (didn’t read) |

| arXiv:1905.05721 (Science) | 20-qubit entangled states, spatially-separated entanglement |

| arXiv:1908.06101 | quantum gates (this paper) |

Also in this presentation is a related work by Mark Saffman’s group [arXiv:1908.06103] which was authored by good ol’ Trent (UIUC ‘16)!

The physics

Here I’ll give a fast explanation of what’s going on in this paper. The system is an array of single atoms trapped in optical tweezers, and the interactions between the atoms are mediated via Rydberg excitations.

Breaking that down:

- Neutral atoms can be trapped in focused beams of light (optical tweezers) which can hold as little as a single atom each. This is probabilistic, and you can take a picture to see which tweezers have 1 atom vs. no atoms, and rearrange. And the atoms need to be cold enough to get trapped, which usually means cooling to ~microKelvin (?).

- A tweezer array can be made with many laser beams, usually one laser through a diffractive element.

- Rydberg atoms are atoms that are almost ionized, with their valence electron out really far from the nucleus. This prevents nearby atoms from also exciting to a Rydberg state (Rydberg “blockade”).

As for the quantum gates part… they choose their qubit to be two internal spin states of the atoms, $|0\rangle$ and $|1\rangle$. There is one laser which addresses transitions between these two, and one laser which adds a phase to $|1\rangle$, realizing single-qubit $X$ and $Z$ rotations, respectively.

For multi-qubit gates, they use the Rydberg blockade to great effect. They have a laser which addresses transitions between $|1\rangle$ and the Rydberg state $|r\rangle$. This can be done locally to individual atoms/qubits, but they do everything in this paper with a global Rydberg laser that addresses all qubits simultaneously.

They use this and single-atom addressing to realize controlled phase, CNOT, CCZ, and Toffoli gates, and build entangled Bell states with high fidelity. It’s interesting to note that by making Toffoli or CNOT and Hadamard, they’ve made universal quantum gates which could be used repeatedly to make any quantum circuit.

The CZ gate

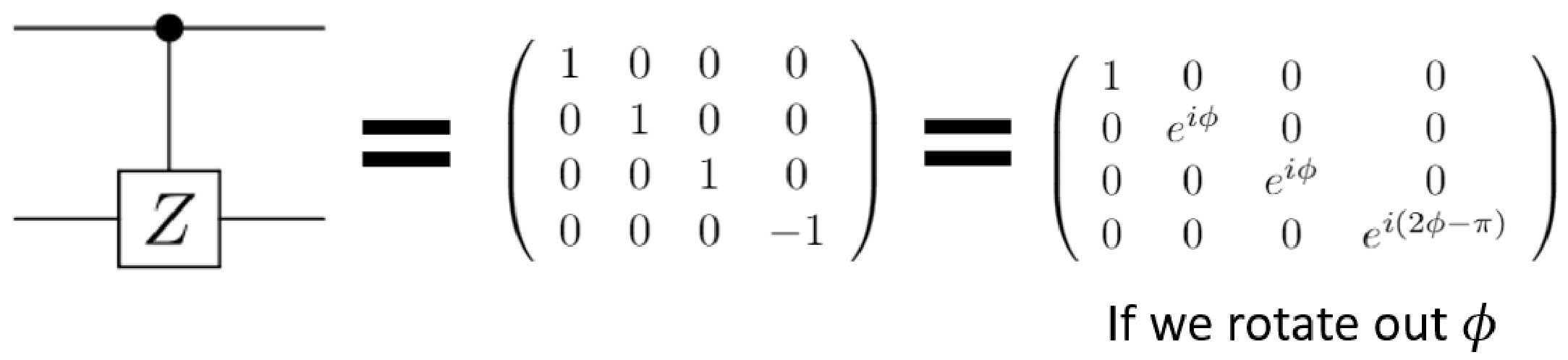

The key physics, I think, is contained in Figure 2 of the paper, which talks about how they make the controlled phase (CZ) gate. The idea is to make a 2-qubit gate that achieves a phase flip only if both qubits are $|1\rangle$, a matrix which looks like:

A graphic from my presentation

A graphic from my presentation

where $\phi$ can be rotated out with single-qubit phase gates.

To get to this matrix, we want to apply phases to the qubits by applying pulses that address the Rydberg transition ($|1\rangle \rightarrow |r\rangle$), which can also be seen as a rotation on the Bloch sphere. As an atom undergoes this rotation, it picks up a phase depending on the path it travels (the enclosed area of the path). The plan, then, is to pick up some phase $\phi$ if one of the two atoms/qubits is in $|1\rangle$, and a different phase if both qubits are in $|1\rangle$.

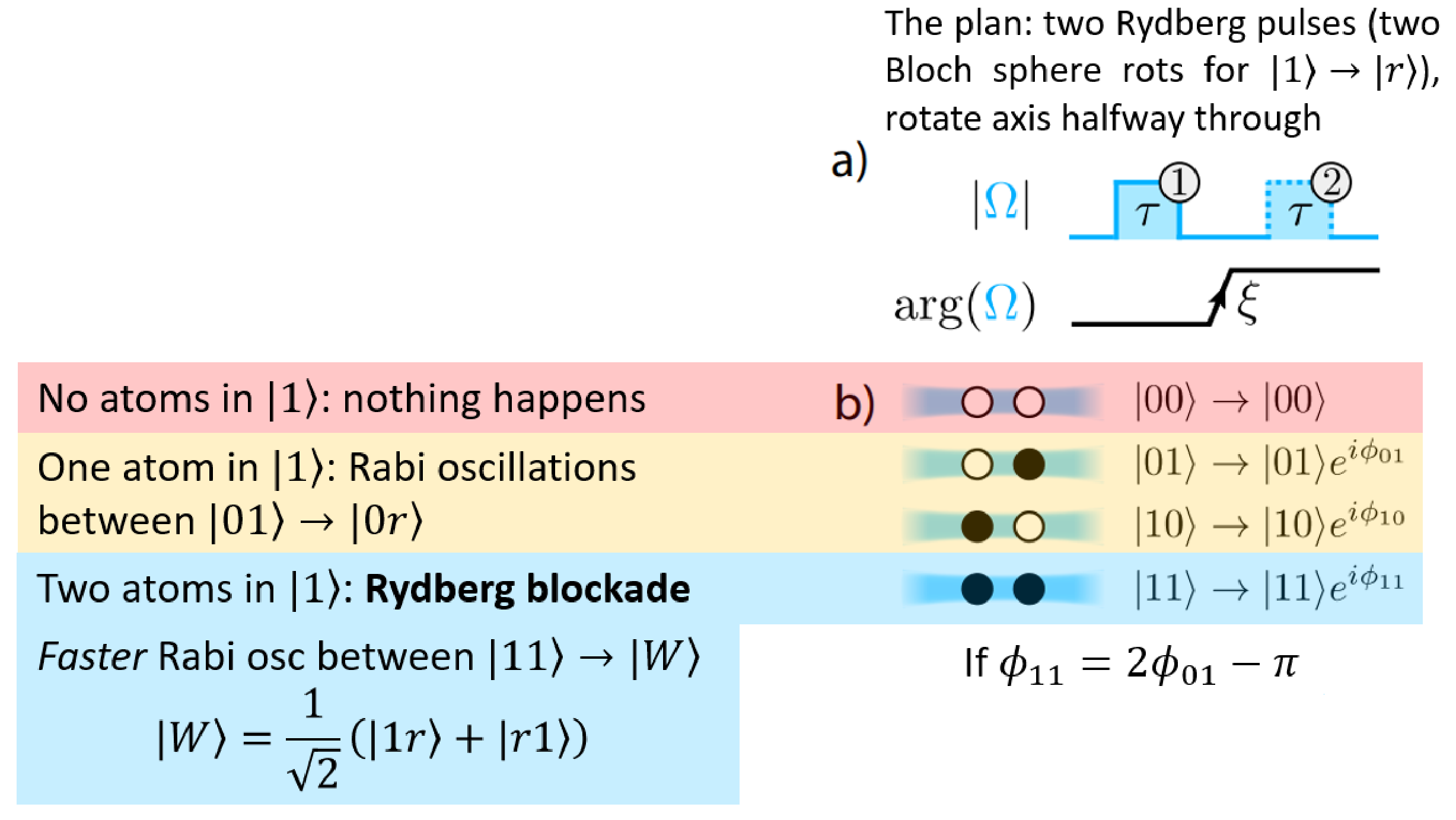

The way they do this is by applying two pulses with a phase shift in between, or applying two rotations and shifting the rotation axis in between…

Another graphic from my presentation, feat. Fig. 2

Another graphic from my presentation, feat. Fig. 2

- The pulses address only qubits in $|1\rangle$, so if both qubits are in $|0\rangle$, nothing happens.

- If one qubit is in $|1\rangle$, then it gets addressed by the pulses and oscillates between $|1\rangle$ and the Rydberg state $|r\rangle$ at some [Rabi] frequency.

- If both qubits are in $|1\rangle$, then the Rydberg blockade happens: only one can be in the Rydberg state at any time. This ends up as a superposition of the two possibilities $|1r\rangle$ and $|r1\rangle$, with some increased [Rabi] frequency.

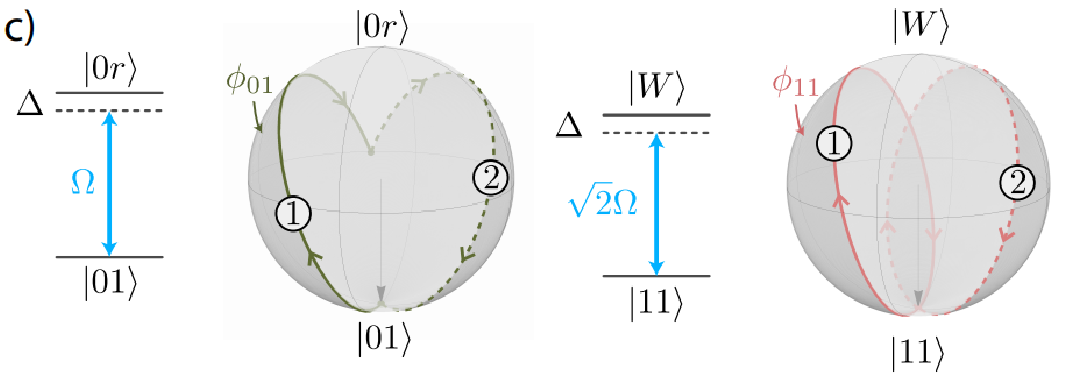

The key here is the difference in Rabi frequencies/rotation rates for $|11\rangle$ vs. $|01\rangle$ and $|10\rangle$:

Fig. 2(c); I don’t know why this is so blurry…

Fig. 2(c); I don’t know why this is so blurry…

One well-timed pulse of the Rydberg laser causes $|11\rangle$ to rotate fully about the Bloch sphere, but $|01\rangle$ only rotates partway. So, by changing the rotation axis, we can do another full rotation for $|11\rangle$ and a different partway rotation for $|01\rangle$ which brings it back down. So by traveling different paths, the states $|01\rangle$ and $|11\rangle$ acquire different phases. By tuning the rotation axes precisely, this can be used to match the matrix up top.

The authors went on to use this to make a 2-qubit entangled Bell state with some pretty high fidelity, and tacked on some more gates to make a CNOT. They also went ahead and made a 3-qubit version of this trick, also with global fields (!!!), and a Toffoli off of that.