My Work #X: everything else

Because I wrote a very long explanation about my first work, here I’ll overcompensate and write a very condensed review of the rest of the work I’ve done. In some sense, this accurately reflects my talks and presentations of my work: half of the time is necessarily devoted to explaining the momentum-space lattice (MSL) platform, and the actual experiments get squished into the second half. Of course, this never fails to glaze eyes so I expect this post to do the same.

Quick momentum-space lattice overview

The point

We want to study quantum systems, which are hard to simulate with the limited computing power of classical computers. So what better way to study quantum, but with quantum? The buzzword here is quantum simulation.

So, we take atoms and put them in a (optical) lattice, so that it’s a quantum particle seeing a periodic potential. This mimics any lattice system, like electrons in a solid, where the periodic potential comes from the regularly spaced atoms (nuclei) of the solid. And because this atom+lattice system is really tunable, it can also be used to study lattice systems that you can’t really create in a real material.

The setup

The usual way to make an optical lattice for atoms is to shine a laser beam at the atoms, and put a mirror on the other side. This makes a standing wave, and if the laser frequency is just below some internal transition of the atom, the atoms see a periodic potential.

Alternatively, and more arduously, you can shine individual (optical trapping/tweezer) laser beams for individual lattice sites. So for example, you can trap one atom with one beam, and another atom in a second beam. If these beams are close enough, the atoms can tunnel between these “lattice sites”, and by adding more beams, you add more lattice sites to make a full lattice.

What we do is similar, but instead of connecting atoms in different spatial positions, we connect atoms with different momenta. These momentum states of the atoms have different energies, so we can connect them by tuning our laser fields to the appropriate energy/frequency differences between the states. This momentum-space lattice technique allows for even finer control over the lattice parameters as compared to real-space lattices, letting us perform studies that other groups would find hard or impossible to do.

The works

1. Quantum walks [arXiv]

I already wrote about the first paper, which was on quantum walks and a sort of proof-of-concept paper.

2. SSH model: topology in 1D

We made a lattice with alternating tunneling link strengths (Su-Schrieffer-Heeger model) and showed its topological properties. In general, something is topological if you need to make a measurement of the entire system to figure out what’s going on, rather than a local measurement. This often translates into “stuff on the edge of the system is different from stuff in the bulk.” In 2D this shows up as conducting states on the edge and insulating states in the bulk.

In 1D, the “edges” are the lattice sites at the end of the lattice, and we showed that these sites support localized states while the bulk shows delocalized, conducting states. This was the first cold atom realization of the SSH model, and was the first big physics goal for the MSL system.

3. Topology in 2D

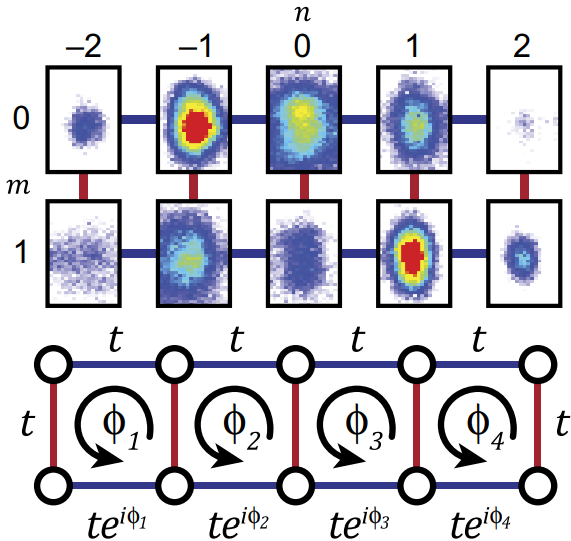

Here, we made a “2D” system with topology, mimicking the behavior of an electron on a lattice under a magnetic field. This is the (integer) quantum Hall system, where electrons in the bulk undergo localized orbits while electrons on the edge flow around the edge in “chiral currents.”

A “2D” system, with data!

A “2D” system, with data!

Experimentally, this was a lot tougher than the 1D studies we had done previously, and we had to introduce a second laser for the lattice in the second dimension. The experimental challenges (lack of laser phase stabilization…) also meant that I had to limit my system to a tiny, tiny 2x5 geometry, meaning that the system was all edge and no bulk. Still, we showed that we could vary the effective magnetic field strength and control which way the edge currents ran (clockwise or counterclockwise).

Another cool thing we did was combine a topological region with a non-topological region, and we showed that atoms would “bounce” off the barrier between the two, despite having no sort of wall or potential difference between the two.

4. Different forms of disorder

In addition to studying topology, we also wanted to look at disordered systems. Here, we implemented two different forms of disorder: quasiperiodic site-energy disorder (Aubry-Andre model) and tunneling phase disorder that varies in time (mimicking coupling to a thermal bath). The first showed total localization with increasing disorder, and the second showed diffusive behavior indicative of a classical random walk.

This was the beginning of my long affair with the Aubry-Andre model, which exhibits a localization transition at some finite disorder strength.

5. Interactions [arXiv]

Atomic interactions are what make quantum simulation “interesting” – without interactions between particles, you can exactly solve and describe the system with something like Mathematica, which defeats the purpose of going to a quantum system. However, it wasn’t obvious that interactions would play a nontrivial role in momentum space.

Turns out, they do. Due to quantum statistics, you get more interaction energy between distinguishable particles than between indistinguishable particles, etc. … so you can say that atoms in the same momentum state feel an attractive interaction. We verified this experimentally!

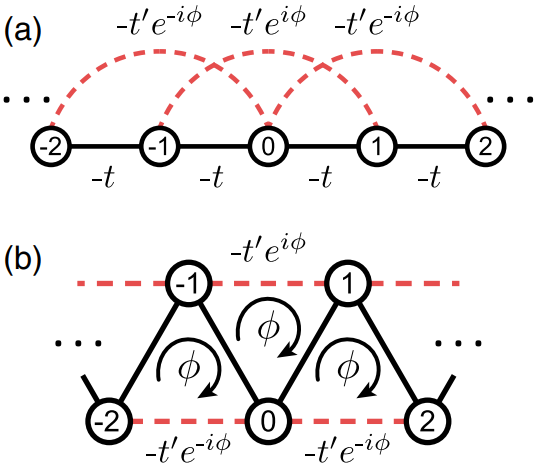

6. Zigzag lattice

A zigzaggy lattice

A zigzaggy lattice

This was a sort of meandering study that was the second step of my inescapable affair with the Aubry-Andre model. On one hand, we made the first “zigzag” lattice in cold atoms (b) out of a 1D lattice with next-nearest-neighbor links (a). This was similar to paper #3 since it was another ladder with topology.

To spice it up, we added Aubry-Andre disorder, to look at the combination of disorder AND topology. While a total 1D disordered system showed localization for all energy states, this zigzag system showed localization happening at different points for different states. This behavior of state-dependent localization is called a mobility edge.

7. SSH + disorder [arXiv]

Maybe besides paper #2 on the SSH model, this has been the biggest result of our lab, and the coolest. Topology is known to be robust to disorder: if you disturb a topological system a bit, the topological character stays put. Of course, if you add too much disorder the topology dies out.

But, it turns out that under certain parameter values, the SSH model can go from non-topological to topological by adding (tunneling/off-diagonal) disorder, which is totally unintuitive. We made and measured this “topological Anderson insulator” in experiment!

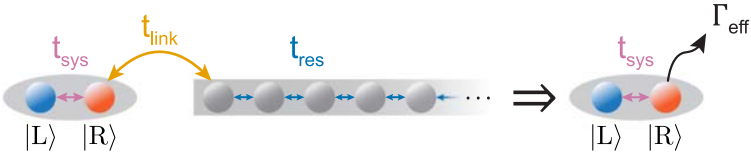

8. Losers

This was a quick computational + experimental project on implementing particle loss in our system. Basically, we can create a lattice site with “loss” by really strongly coupling that site to a reservoir. This picture will explain it better than I could ever do with words:

A lattice with a loser, $R$

A lattice with a loser, $R$

There’s some scientific basis for calling this lossy lattice site a loser, though I didn’t sneak that into the paper.

9. Collective spin [arXiv]

Don’t ask me about this paper.